One question that loops endlessly on writers’ forums is “How can I sell more books?” The question is a natural one, but for many self-publishers, it betrays a certain lack of awareness about the publishing business. Lest I sound holier than thou, let me clarify that my own book sales stats are probably no better than yours. I write, I publish, I make my books available, and I hang on to my day job. This article isn’t about magic marketing techniques or search engine secrets; it’s about making a realistic assessment of your potential to make money as an indie publisher.

One question that loops endlessly on writers’ forums is “How can I sell more books?” The question is a natural one, but for many self-publishers, it betrays a certain lack of awareness about the publishing business. Lest I sound holier than thou, let me clarify that my own book sales stats are probably no better than yours. I write, I publish, I make my books available, and I hang on to my day job. This article isn’t about magic marketing techniques or search engine secrets; it’s about making a realistic assessment of your potential to make money as an indie publisher.

Self-Publishing: Business Basics

Smart product developers—and books are products—start by identifying the needs of a customer group. They develop products specifically to meed those needs and they mitigate risk by using surveys and focus groups to estimate how many people will buy their product at what price. How many kayakers will buy a lightweight folding paddle at $500? How many will buy it at $100. What is the cost to manufacture the item in quantity? Can you sell direct or will you have to sell wholesale to a distributor who will double the price and then pass the item to a retailer who will double it again? What will it cost to advertise? Clearly, the product developer needs more than a great product. Market research and business strategy are key elements of success.

Compare this to the business plan of the average indie novelist: “I just finished a new book. How can I get readers to buy it?”

Self-Publishing: Costs

Consider the expenses involved with creating a novel. For the sake of discussion, I’ll make my estimates on the low side. Assuming your computer and word processor and your desk and writing space are paid for by outside interests, how many hours does it take to write and polish a manuscript? Writing time will vary greatly from writer to writer and book to book, but let’s assume it takes 500 hours to produce a finished manuscript. At $10/hour (which is an insult but you can adjust the figure to suit your own calculations), that represents a $5000 investment. Let’s assume $1000 for editing and proofreading and another $1000 for design and typesetting (also low estimates). For Copyright, ISBN numbers, printer setup and proof fees, let’s add in another $300. Toss in $200 for eBook production. On the low end, it costs $7500 to produce a quality book.

It’s no wonder self-publishers often write off the value of their own time and bypass the important contributions of editors and book designers, but that’s not a realistic approach to any business. If you want to “get your book out,” you’re an artist; practical considerations are irrelevant, but if you want to make money in publishing, make a business plan like you would for any other retail product. Calculate how much you’ll need to invest and how much you’ll need to recover to break even.

Self-Publishing: Assessing the Break-Even Point

Your customer will likely purchase your product from a retailer who keeps 50% of the list price as a commission. Let’s assume your book retails for $20. The remaining ten dollars goes to your POD printer/distributor who deducts manufacturing and shipping costs. Assuming you didn’t get scammed by a vanity press that deducts an additional “publisher’s” royalty, you probably make about $5 on each book. In other words, you need to sell 1500 books to break even. EBooks will change the equation somewhat. Assuming your eBook is priced at $3.00 and retailers take 30%, your profit will be roughly $2.00 per book (less your costs). If you offer eBooks only, you have to sell over 3500 copies to break even. Whatever the ratio of eBook sales to paper book sales works out to be, you have to sell a lot of books before you’ll see black ink on your spreadsheet.

Self-Publishing: Pricing

Apple changed the music retailing game forever when it established that a “tune”—whether it’s two minutes of talentless screeching or a virtuosic orchestral performance is a one-dollar commodity. The book business is not quite so price-fixed, but traditional price ceilings govern the market. Unless you’re offering a “coffee table” art book, charge anything over $20 and sales prospects diminish rapidly. Debate over what the “correct” price should be for eBooks is ongoing. Unless you have an established reader base, anything over $5 will stall eBook sales. Some argue that $3 is top tier for indie publishers.

With most retail products, developers consider the cost of bringing a product from concept to the retailer ’s shelf, and then set their price to make a profit. In publishing, the retail price is largely predetermined. Opportunities are squeezed between the market price and the costs of development and distribution. Publishers do sell books in sufficient quantities to make their businesses viable, but if you want to get into retail, you’ll find thousands of products that come with less competition and fewer price constraints. Books? Unless you have a solid plan, selling yachts, real estate and luxury cars will bring better returns.

Self-Publishing: Choosing a Target Market

Smart product developers don’t launch a product hoping someone will buy it, and neither do smart publishers. Customers buy products because those products serve a need; publishers work hard to identify and fulfill those needs.

Nonfiction publishers are the most pragmatic. Books about the latest version of Photoshop or how to service your own bicycle provide practical value to clearly identified groups of readers. Need to learn PHP or how to replace your Toyota’s headlight bulb? The practical benefits of a useful book far exceed its purchase price.

Fiction is a far less practical product (though no less valuable). Smart publishers capitalize on popular markets. Books with crime, mystery, vampire, romance, science fiction, old west and other themes appeal to dedicated reader communities. Genre fiction writers study what’s popular and successful with their target audiences. They develop characters and stories that resonate with readers and (hopefully) sell.

Art is essential and potentially worth money, but unless it’s specifically commissioned by a client, it’s rarely developed as a commodity. Artists paint, sculpt and write fiction in garages, basements and home offices all over the world. Some of these people are brilliant at what they do—and many of them dream of selling their work—but they create primarily because they’re artists; they’ll paint, sculpt or write whether they get to share their work or not. If having your book referred to as a “product” smells slightly offensive, you’re probably an artist.

Understanding where you lie on the spectrum between artist and entrepreneur is critical to publishing success. Success for the business investor is measured on a balance sheet. Success for the artist corresponds to personal satisfaction with the finished product. By all means, publish your work and offer it for sale. You can even fantasize about being one of those lucky indie writers who gets “discovered” and has their work go viral—it does happen. But before you go into the publishing business, be realistic about your odds of profitably selling a cheap retail product to an unidentified or general audience without the endorsement of a major publishing house or a celebrity. Publishing art is a noble and important endeavor, but it’s usually a ridiculous business proposition.

Self-Publishing: Distribution Channels

Physical bookstores are facing challenges these days, but they’re generally off-limits to indie publishers anyway. (Bookstores have plenty of good books to choose from without having to sort the shinola out of the enormous pile of self-published offerings). Indie publishers take advantage of easy access to major online bookstores, but these are “passive” channels. “Passive” distribution places your product where it can be found by people searching for it. “Active” distribution places you and your work directly in front of prospective readers.

Do you have a consulting, speaking or contracting business? If so, a book may bring you added credibility that pays off—even if you lose money on your books. Do you have ready access to a community of cyclists, canoeists, javascript programmers or flamenco enthusiasts with whom you can build relationships and promote your books? These active channels are much more accessible to self-publishers who know where their readers gather on the web, but be realistic—you won’t easily sell 1500 books on acoustic guitar forums. If you’ve written a book about sailing, yacht clubs may be happy to have you as a guest speaker but consider whether selling a dozen books at a presentation will make a dent in your original investment—or is even worth your time.

I know a speaker who has spoken to groups as large as 20,000 people and sold as many as 1000 books at a single keynote address—that’s $20,000 in gross sales at one event. Conversely, his Amazon sales amount to about a dozen books each year. This writer is the perfect candidate for self-publishing; a publishing house would bring him no closer to his audience and would only cost him money. Just as important, he’s not primarily in the bookselling business; his book and video products are ancillary to his primary speaking business. This writer is well-positioned to profit from direct sales, but his circumstances are hardly the norm.

What is your business—really? Are you selling book products or are you selling services? Cutting out bookstores and their 20–55% sales commissions can reduce the number of book sales required to break even by half, but even then, will you be able to move 750 books without investing a huge amount of additional time?

How Trade Publishers Succeed

Trade publishers leverage a network of bookstores and review sources they’ve built up over decades. They operate at a huge scale where they print and warehouse tens of thousands of books at a time at costs per unit that are well below what the average POD publisher pays. As volume shippers, they get huge discounts on moving boxcar loads of product.

A publisher’s catalog can be thought of as a sort of “mutual fund” of books. Perennial, seasonal, and cult favorites deliver a certain level of base profit; the Harry Potter books, The Wizard of Oz, a selection of reissued classics by Dickens and Melville, Dr. Seuss, Disney Princesses, novels by King and Kingsolver, books tied to hit movies—bookstores can be counted on to keep all these in stock. Each may trickle out of stores, but together, they represent a river of books that sell. New authors are cherry-picked from thousands of offerings, hyped and rotated into stores for a 90-day spin. Most end up backlisted—they cost publishers more in returns than they make in earnings—but one blockbuster can turn into Fifty Shades of Profit.

Publish with Realistic Expectations

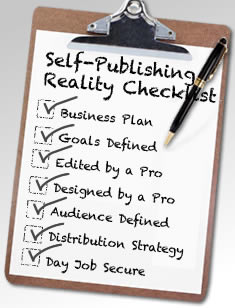

Publishing a book? Here’s a short list of items to add to your reality checklist:

Define Success. If you’re an artist and you want to share your work, spend what it takes to get your manuscript professionally edited, typeset and cover-designed (there’s nothing more tragic than shoddy art). Release your book into the wild and then go write another. Don’t transform yourself from a first-rate artists into a third-rate marketer. If you want to succeed as a bookseller, develop a business plan before you write your book.

Calculate Your Costs. Professionals know that time is money. Writing and research time are investments as much as editors, designers and printers. Publishers who write off their time but claim success after selling a few hundred books are worshiping false profits.

Know What You’re Selling. Low book revenues may not matter if your book gives you the credibility to sell other more profitable services. If you’re a motivational speaker, a consultant, or a book designer, a few new contracts may more than offset your original book investment.

Know Your Audience. As an artist, you may wish to simply write a book that satisfies you. As a publisher, consider whether your readers like genre fiction, want new technical skills, need to lose weight, or want to appraise their watch collections. Write a book that addresses a need that’s either unmet or that you think should be approached in a new way.

Consider Distribution Channels. With physical bookstores off the table, figure out who your target readers are and make a plan to put your book in front of them. Usually, this outreach requires a combination of Internet forum participation, personal appearances, advertising, blogging, and use of any number of other channels. When direct sales aren’t possible, know who will be selling your book and what size slice of your pie they’ll be taking in return.

Diversify Your Holdings. Trade publishers understand that even excellent books often don’t make it—for any number of reasons. They offer dozens of new books every quarter based on tried-and-true success formulas along with a few by risky new authors. Though it’s difficult for self-publishers to operate on anything approaching that scale, consider writing a few nonfiction books to help offset probable losses from low sales of your novels. You can be both artist and entrepreneur if your business plan adjusts its expectations across a range of offerings. Also, more books means more opportunities to establish a foothold with a reader community. If any one of your books becomes popular, it will catalyze sales of the others.

Plan Your Route. Whether you self-publish or try to get picked up by a major publisher, understand that each route has advantages and liabilities. Trade publishers generally issue polished products through a network of reputable booksellers. They pay advances and if your book succeeds, it can succeed wildly. On the other hand, trade publishers assume a degree of creative control that some creative writers don’t want to give up. If your book doesn’t move, it can disappear forever into the black hole of the publisher’s backlist catalog. Self-publishers retain all their rights and full creative control, but the up-front investment and all ongoing expenses are entirely theirs. Self-publishers do best when they have ready access to a willing audience that a generalist publisher wouldn’t be qualified to communicate with.

Don’t Stop Dreaming. In spite of all the practical advice offered here, the eddies and currents of the literary business world sometimes carry a small book into big waters. Though the odds are slim, indie books occasionally become enormous viral successes. It may be worth it to buy a lottery ticket or two; just don’t spend your grocery money on a longshot.

Whatever You Do, Do it Well. Whether your book is a heartfelt personal memoir or a soulless commercial product, don’t skimp on quality—your book has your name on it forever. Writers who bypass editors, typesetters, and designers only reinforce the stigma that all self-published books are crap. Mediocre writing and design will increase neither your professional credibility nor your chances of success. Trade publishers print books in huge quantities; they save money by using smaller type, tighter leading (line spacing), and narrower margins. Self-publishers can exceed industry design standards for pennies per book, but few do. Whatever happens to your book in the world of commerce, set yourself up to take some small satisfaction in knowing you gave it your best.

Plan your publishing journey with care. Go forward with an understanding of the challenges you’ll face. Publishing is a tough business but it’s a great one for those who don’t run aground on the rocks of unrealistic expectations or get lost in the fog of nebulous business plans. And take heart—it’s better to have published and lost than never to have published at all.