Zero, Infinity, and the Search for Meaning

13.7-billion years ago, the universe expanded from a single point. Some of the light we see in the sky took billions of years to travel across space—at 186,282 miles per second—to reach our eyes.

Will the universe expand outward indefinitely—infinitely?

Or will it slow down, reverse course, collapse into a single point—zero—and explode again?

Of course, numbers like 13.7-billion and 186,000 are incomprehensible.

Most people’s brains are capable of identifying no more than five objects at a time. We might recognize 12 or 15 if we can distinguish groups of 3 or 4 or 5, but our capacity to distinguish 5,234,701 from 12,862,223 is nonexistent.

Nonexistent?

Nonexistence is zero.

Nonexistence is an Essential Absurdity—an intellectual carrying handle for something otherwise too big (or too small) to lift. We speak of “zero,” and believe we understand it when we conclude that (apart from this example), the word “dog” appears zero times on this page. But in that case, we must first imagine that the word exists and then intellectually erase it. There is no “zero” without a “something” that’s been deleted; we must state or create whatever it is there’s to be zero of. (Possibly, you even pictured an image rather than the word.)

Because our brains can manage the number one, words like “truth,” “love,” “God,” and “beauty,” allow us to collapse the infinite into a single point. The concepts those words stand for—the Essential Absurdities—lie as far beyond rational definition as the outer fringes of the universe, but we share and use and rely on them. They drive our innate search for meaning—which is an Essential Absurdity in itself.

And this leaves us—with brains capable of grasping three-to-five—to ponder the vast, infinite mystery. As storytelling beings, we gaze at infinity and zero through a hazy lens of ideas, emotions, biology, memories, philosophical constructs, science, and insights—as if knowing about quarks, dopamine, Shakespeare, Leo Kottke, the rules of rugby, how to rebuild a carburetor, and mitosis will bring us meaningfully closer to understanding “the big picture.”

Ironically, it is that fruitless quest to comprehend the incomprehensible that gives our lives meaning.

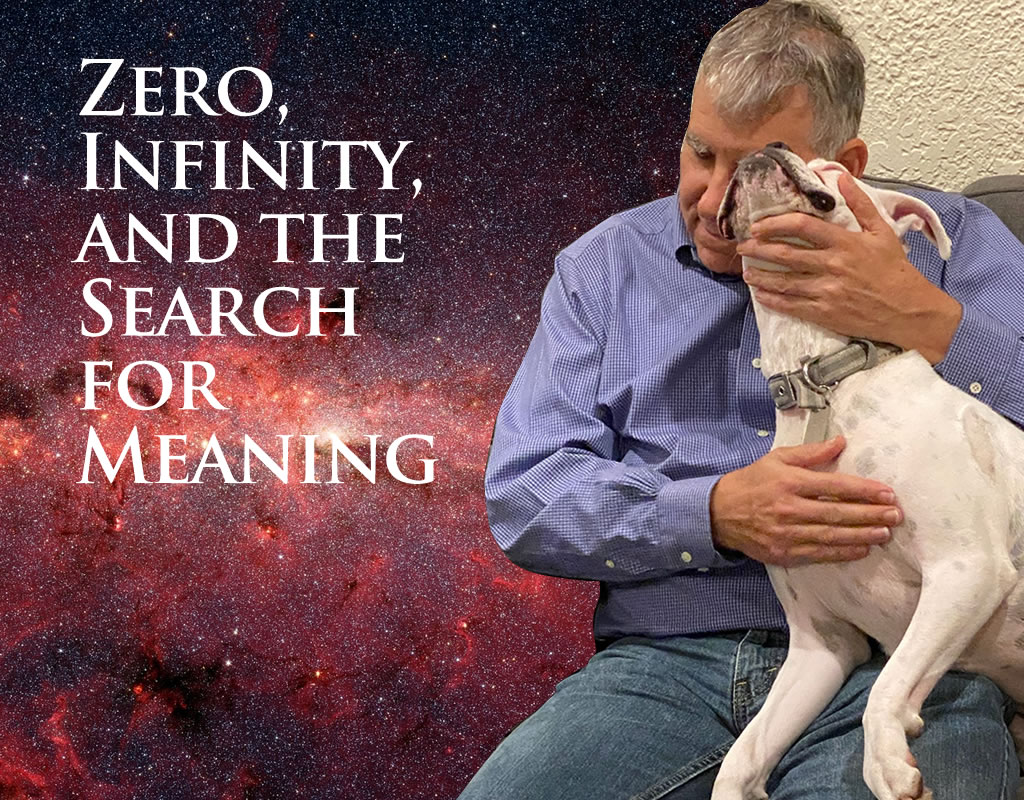

Yesterday, I found my boxer, Lulu, lying in the yard, barely breathing. By the time I got her to the veterinarian, she was gone—non-existent—zero—except for her physical form, a broken container for infinity. The doctor said it was likely a blood clot or aneurism.

This morning brought zero cold noses pressing on my hand as has been the morning custom these past seven years. There are zero ears to scratch. Zero pairs of eyes look up into mine to celebrate the mystery. Zero fills my heart.

And as I gather the memories I will intellectually visualize and delete over and over in my quest to comprehend zero until my spirit tires of the exercise, I will miss my daily glimpse of infinity.

(No condolences needed, please. Go hug your pet or your loved one!)