Problem-Solving & Storytelling: Understand Their Story

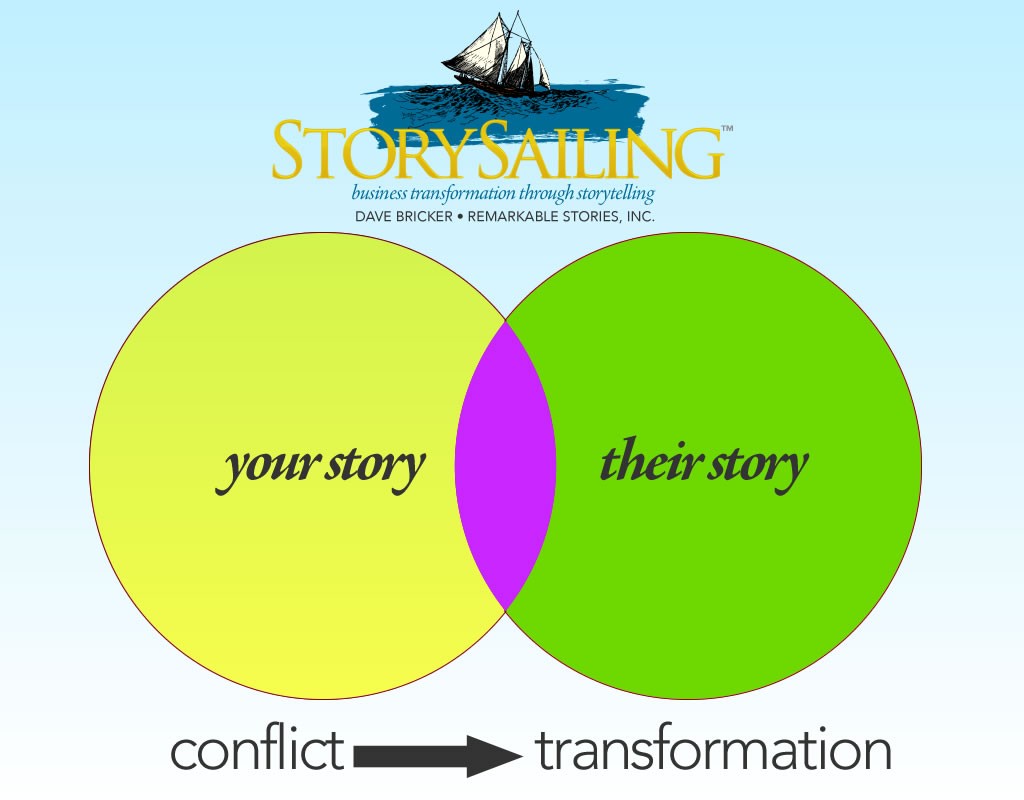

Use storytelling for problem-solving. Think about the various stories involved in a conflict and plot a course for resolution. Seen through the StorySailing™ spyglass, a story is analogous to the voyage of a sailboat across the rocky, stormy seas of conflict to the safe port of transformation. Too many stories end poorly because the captain insists on heading deeper into a storm.

Use storytelling for problem-solving. Think about the various stories involved in a conflict and plot a course for resolution. Seen through the StorySailing™ spyglass, a story is analogous to the voyage of a sailboat across the rocky, stormy seas of conflict to the safe port of transformation. Too many stories end poorly because the captain insists on heading deeper into a storm.

I designed a piece for a client and somewhere between the printer’s confusing online ordering system, the final result differing from the very clear mockup I sent, my failure to see that the misprint was visible on the digital proof they sent back, and their production people failing to notice that nobody would ever intentionally specify such a tasteless design element in a high-end piece, the job got bungled. I asked them to reprint the job. The printer said it was my fault.

PROBLEM-SOLVING: ACCOUNTABILITY

Whether or not I was the one who screwed up, they were right. One thing I learned from my years of sailing is that whatever happens on-board my boat is my responsibility—essentially my fault. Captain Smith was asleep in his bunk when the Titanic hit the iceberg. He was standing in the wheelhouse when the ship went down. My client had paid for printing. I was in charge of delivering results, not excuses. I wasn’t about to start whining to them about the printer, and this meant I was potentially on the hook for the cost of a reprint. Thus, I found myself adrift in the rocky, stormy seas of conflict.

After a few email exchanges, the stormy weather hadn’t changed and neither had my client’s deadline. I studied the wind and waves and adjusted my sails. How could I steer my ship away from conflict toward resolution? I needed a problem-solving strategy.

PROBLEM-SOLVING: MAKE IT PERSONAL

Forget email; nothing beats personal interaction. My first step was to call, wait on hold for a while, and connect with Shannon, a real, live, human customer service person.

Anyone who has ever worked in customer service—especially on the phone—will tell you they deal with irate and unreasonable people all day. I resolved to be the exception—the bright spot in Shannon’s day. I tried to be that customer she really wanted to help.

As you might expect, Shannon had no decision-making power; she had to go back and forth to her manager at every phase of the discussion. Each time, she put me on hold for several minutes. Each time, I had to listen to their cheeseball on-hold music which was cranked up loud enough to distort my phone speakers. Every time Shannon came back, she apologized for the long delay. They were burning up my time, and she knew it. But I focused on the outcome—on the hoped-for transformation. If the delays made her feel more obligated, that was fine with me.

Each time Shannon apologized, I reassured her that I knew she was stuck in the middle, that I knew she was working hard to help resolve the problem, and that my grievance was not with her. I was that “nice guy” she wanted every customer to be.

I did have a few aces to play. I could have reversed the credit card charges and found another vendor. I could have threatened to write bad reviews on Yelp and Google and Facebook. But threats would have escalated the conflict—not an ideal problem-solving method. And I would have had to pay another printer full fee to redo the job. I asked myself what my ideal outcome was. Where was the “safe port” in my story? Where did I want to steer my ship? What transformation would be an ideal ending for me? I wanted the job reprinted at no cost, and I wanted to be able to keep using this vendor. I’d used them for several projects, and when they get it right, the results are magnificent.

PROBLEM-SOLVING: SAIL AWAY FROM THE STORM

Rather than pointing my ship deeper into the storm, I decided to write a success story.

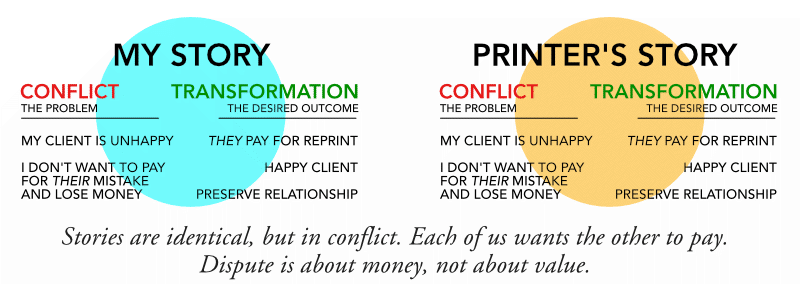

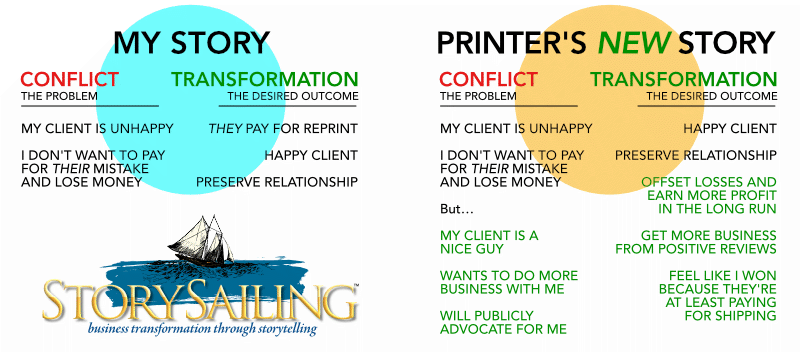

To accomplish this problem-solving goal, I had to consider their story. Regardless of whether the problem was my fault or theirs, I knew they didn’t want to reprint the job for free. That would represent a loss to them. How could I add value? How could I establish that their relationship with me was worth preserving?

I changed their story. I pointed out that though I wasn’t a large account, I was a repeat customer. I mentioned a second project I had already placed in their hands. I explained that my client used them every year and would like to continue using them. Eating one project for a small, one-time client would have been a loss for this printer. Eating one project for a client who would continue to use them over and over would be an investment. I established my value. I made them want to keep me.

But if I wasn’t going to send them more money, what else could I do to offer value? How could I help them with a very important transformation—a business outcome that was meaningful to them? I pointed out that their ratings on Yelp, Facebook, and Google, were only “pretty good.” Instead of threatening to post bad reviews, I offered to write thorough, well-explained, five-star reviews on all three platforms. Instead of issuing a threat I made an offer.

Nobody wants to lose everything in a conflict. Sometimes a small concession goes a long way. In the end, I agreed to send back the defective pieces and pay $10 for the shipping of the reprinted work—a small, almost trivial gesture that made them feel like they won something tangible in the negotiation. The printer agreed to redo the order at no cost to me.

I wrote three five-star reviews as promised, and was able to feel sincere about them. I even mentioned Shannon by name. That took fifteen minutes of my time and boosted their social media reputation ratings. Hopefully, it gave Shannon some leverage at work, too.

Story conflict lies at the root of many of the world’s ills; two people see different problems and want different outcomes, and the next thing you know there’s war. Everyone ends up in the middle of the ocean firing cannons at each other. But those who disagree with you have stories of their own; sometimes those stories are rational and reasonable. Use storytelling techniques for problem-solving. Go beyond the blame game, and consider how your story differs from their story. Understand their story and find ways to offer value that offset any losses you want them to incur on your behalf. Offer them a better transformation, and make reasonable concessions. No one will negotiate if they end up feeling like a loser. Calm the seas, moderate the wind, sail away from the lightning and thunder, and continue your journey. Helping opponents navigate toward their safe port of transformation is often the best way to resume sailing toward your own.