Indie publishers are everywhere and so are indie bookstores, but apart from their names, the two have little in common. “Independence” is a feelgood concept, but it’s often presented without any reference to that which a publisher or bookstore is independent from. Therein lies the difference. Does “independent” really mean anything in today’s publishing world?

Indie publishers are everywhere and so are indie bookstores, but apart from their names, the two have little in common. “Independence” is a feelgood concept, but it’s often presented without any reference to that which a publisher or bookstore is independent from. Therein lies the difference. Does “independent” really mean anything in today’s publishing world?

Independent publishers are independent from the Big Six publishing establishment, but not being affiliated with six entities isn’t much of a distinction. For publishers, independence comes with a price. After writing, indie publishers must work independently with editors, designers and printers. They must make their own arrangements with distributors of print and ebooks. Perhaps most importantly, they must independently assess whether books they have a great personal stake in are viable products. Indie publishing isn’t better or worse than traditional publishing. There’s much to be said for having someone else push your manuscript down the long road to bookstores and there’s much to be said for cutting out the middleman and keeping creative control over your work.

Indie publishers generally sell books to niche audiences in lower volumes. They usually offer one or just a handful of books. Unlike big publishers, they aren’t able to circulate and promote hundreds of books until they find a blockbuster that pays for all the ones that don’t sell, but they are often positioned to make a profit with very low sales volumes.

Independent bookstores are independent from big bookstore chains. Does that mean anything? The only big bookstore chain left is Barnes and Noble, and it appears to be herding customers toward its online outlet by pushing its Nook hardware. Having seen the demise of its rival, Borders, we can assume B&N is planning its future very carefully. We can also assume pretty much every other bookstore is an indie bookstore by virtue of not being a Barnes and Noble—not much of a definition.

Of course, they’re all independent from Amazon.com. Amazon carries 32.8 million titles while the average big bookstore carries 70,000 books—not unique titles—books. Factor in free shipping (for Amazon Prime members), no sales tax, user reviews and the convenience of shopping from home, and few excuses remain to shop anywhere else. Bookstores from Barnes and Noble to the neighborhood newsstand are wondering how to stay relevant … and open; $4.00 brownies and lattes are only going to take a bookstore business so far.

Though the business landscape is frightening, it would be a shame to see small bookstores perish. Bibliophiles still love bookstores and paper books. Not everyone has yielded to the compelling convenience of a Kindle. There’s a certain romantic aspect to being surrounded by all those stories, opinions, discoveries and theories and the smell of fresh printer’s ink in a room shared by other thinking, reading people.

Indie Bookstores Can’t be Little League Bookstores

For the most part, indie bookstores order merchandise from the same two big distributors that big stores do. There are huge quantities of trade-published books available for the wholesale cost of 50%-off the cover price; these principally account for bookstore offerings. It makes sense that book retailers will stock these products; a great selection is available and the markup is good. But is it really wise for small bookstores to compete with big ones by selling the same products ordered from the same catalogs? Only to the degree they want to struggle to serve the popular audiences big stores capture more effectively.

Why Indie Bookstores are Independent from Indie Publishers

Assume the average indie paperback costs $20.00. The costs of printing and shipping are about $5.00. The costs of writing, editing and design are usually written off altogether. If a bookstore insists on taking $10.00 for books on consignment, they make more money than the writer/publisher does in exchange for taking absolutely zero risk. (If I paid 50% commissions on my hardcover books, I’d be subsidizing booksellers.) The expected return for selling a few dozen books at a bookstore reading isn’t worth the trip, especially when many online retailers will accept 20% commissions.

This pretty much trashes the relationship between indie publishers and indie bookstores. I’d love to sell books and do readings at my local bookstore and they’d probably love to have me, but we can’t afford each other. Something has to change.

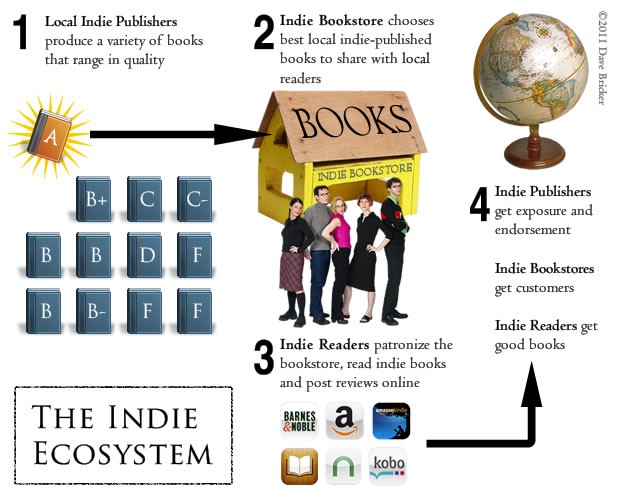

I suggest a new role for indie bookstores that will give them one important advantage over big retailers. Because of exclusive and nepotistic marketing machinery like the New York Times Book Review that favors the interests of Big Six publishers, and the (sometimes warranted, sometimes not) reputation of indie books as amateurish and shoddy, readers have natural loyalties to “real publishers.” But good readers just want good books. As with other products, they want a qualified reviewer to try them first and recommend them or not.

Who would be better qualified to do that than someone crazy enough about books to open an indie bookstore? Big bookstores are all about global outreach, but they have no way to evaluate local talent. Indie bookstores are more likely to be staffed by English majors and less likely to be staffed by retail clerks; they are well-positioned to act as curators for remarkable, high-quality undiscovered books from local writers. (To be fair, there are plenty of wonderful book nuts working at big stores, but these stores are generally not seen by local readers to be consistent sources of good recommendations; the public perceives them to be retailers, not curators.)

A known problem with indie books is huge variance in quality of writing, editing and production. Big retailers don’t have time to sort through the pile, but small bookstores are well-positioned to evaluate, promote and review local writers. They can sort out the junk by looking at the cover art and the typesetting in a few seconds. For those books that pass aesthetic muster, it doesn’t take long to read a chapter or two to see if the writing holds water before diving deeper. When indie bookstores become trusted community resources that find and share (and perhaps even polish) local gems, they will have two things big stores don’t—unique products and the trust of readers who value their recommendations. More than likely, publishers and bookstores will have to split profits instead of list prices, but by putting good writers and good books in front of good readers, indie bookstores will attract people who will buy indie books along with others that are trade published.

Of course, indie bookstores that provide consistently good recommendations will become trusted by other indie bookstores who will then have an easier time building their own collection of high-quality indie-published books to serve their own local indie reader communities.

Independent Readers are the next link in the chain. Indie bookstores should be the catalyst that encourages the crystallization of indie readers—readers who like having the inside track on good things that have flown under the radar of big publishers and popular culture. Like bookstores, these readers have a very special job to do; they can’t just read and run. By shopping at indie bookstores and then posting honest reviews in public places, indie readers support everyone in the independent chain. After an indie bookstore promotes a writer locally, indie readers use Amazon.com and other mainstream channels to spread the word globally.

Bookstores may argue that the end result—publishing reviews and thereby promoting books through big retailers—dilutes the advantage they work so hard to develop, but big publishers work the same way. Books are released, promoted for a few months and then cleared away to make room for new offerings. Let indie bookstores promote indie publishers for a reading or two and then send them on their way armed with sales results, direct encounters with readers and a list of reviews. There is no shortage of good indie books to keep indie bookstores and their patrons occupied and engaged.

In the Indie Ecosystem, everyone can be as independent as they like—with the caveat that there’s no such thing as true independence within an ecosystem; grazers, predators, prey and pests all have important roles to play; none can survive without the others.

- Indie Publishers need Indie Bookstores to thin the herd—to weed out the slow, the weak and the sick.

- Indie Publishers need Indie Readers to buy their books and spread the word through mainstream retail channels

- Indie Bookstores need Indie Publishers to provide them with unique and remarkable products that will bring in customers who want something different.

- Indie Bookstores need Indie Readers because regular book customers can get what they want cheaper and more conveniently elsewhere.

- Indie Readers need Indie Bookstores to find the gems they’re unwilling to risk buying sight unseen from a big online bookstore.

- Indie Readers need Indie Publishers to create books that appeal to niche audiences and books that are too sophisticated, edgy, esoteric or controversial for mainstream publishers to handle.

The publishing climate has changed; things aren’t going back to the way they were. In an evolving world dominated by a few big players, everyone is independent. We’re not going to topple the giants (and I wouldn’t want to; Amazon keeps me blissfully out of the mall every Christmas), but if the independents can recognize their interdependence, we can keep some healthy diversity in a system that has very important things to offer.