Conflict: Sailing the Storms of Life and Business

In storms of life and business, it requires immense energy to sustain conflict. Dangerous and destructive forces require attention and—at the appropriate times—resistance, but often the best strategy is to park and wait for the tempest to subside.

A retail client came to me complaining that her competitor was offering sale prices that had been reduced below her wholesale costs. “If I compete with him, I’ll be subsidizing my customers. I just can’t afford that.”

I smiled at her. “You know what I’m going to do now…”

Janice laughed despite her predicament. “I’m pretty sure you’re going to tell me a story.”

![]()

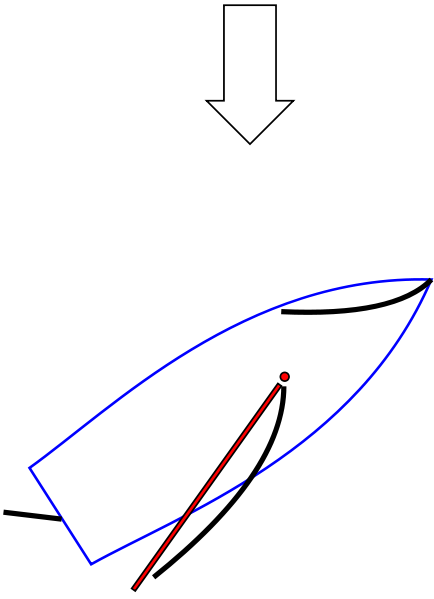

September, 1991. I am standing at the wheel of a wooden boat, surfing down enormous waves and trying to keep from rolling sideways in the troughs. The electronic autopilot has failed. The wind is blowing at least fifty miles per hour. Waves crash over the deck. The cockpit fills repeatedly with seawater. I watch it spiral down the cockpit drains as I struggle to keep on-course with a wheel that takes nine full turns to shift the rudder from one side of its range to the other. Seasick, I tremble, heave into a bucket, and then feel relieved for another half-hour or so until the next bout of nausea grips my stomach. I have never experienced weather like this before. The sky is pewter gray. The air is cold. The waves are rolling black mountains.

But the gale blows from behind us. Gibraltar, our planned destination, lies eight days beyond the horizon.

Steering is an exercise in stamina, concentration, and quiet determination.

Inside the cabin, sea water is forced through the seams of the same decks that kept us dry for the first two-thousand miles of our journey. Our bunks are damp and cold.

Alone in the middle of the North Atlantic, there is no one to call for help, but though we are miserable, we are in no more danger this windy afternoon than we were early this morning when the glass-calm sea we were motoring across began to grow choppy and rough. As uncomfortable as we may be, we are making our way as our boat was designed to do.

But it will be harder to steer at night when we can’t see the big waves. We have made a valiant effort to keep sailing, but this storm could blow for days. If we continue to fight the weather, we risk becoming dehydrated, weak, and unfocused. “We’ve had a good run,” I say to my friend, “but it’s time to park; we should heave to for the night.”

“What’s heaving to?” he asks.

“What’s heaving to?” he asks.

“If we get the back of the boat trying to point us into the wind and the front of the boat trying to pull us off the wind, we’ll sail forward a bit while the wind blows us back a bit. We’ll hover in about the same spot without having to steer or tend the sails.”

He helps me raise the mizzen sail at the stern of the boat. Exhausted, we wordlessly sheet in the sail and bring the bow across the wind, tighten up the jib, and bring the helm over. The forces balance and Journeyman rides comfortably up and down at an angle to the seas.

With hardly a nod, we descend into the cabin and without even taking off our foul weather gear, we fall asleep among the piles of soggy sail bags that shifted onto our wet bunks.

Faint light shining through the ports heralds the beginning of a new day. We slept—not well, but at least we slept—and Journeyman continues to ride in relative comfort at an angle to the swells. I am chilled and my joints ache, but my nausea is gone. I manage to swallow some food and water.

I open the hatch and ascend to the cockpit. To my surprise, the wind has increased. Mountainous swells surround us and as we rise to the summit of one, I watch an enormous gust of wind transform the surface of the ocean into an exploding field of milky white froth.

But as the day wears on, the storm passes; the wind and seas abate.

We continue on. Another week of sailing lies ahead of us.

Wet sailbags, clothes, and gear dry on the cabin top.

We cook and eat.

We take turns at the wheel.

We watch the stars arc across the sky.

We plot tiny eastward-moving crosses on our chart.

![]()

So often we are told to ‘fight to the end.’ ‘Never surrender.’ ‘Never give up.’ But conflict—whether in business, personal life, or nature—consumes energy. Sooner or later, every storm passes. To continue on in the service of some notion of “valor” would have been dangerous. As long as we were too seasick to eat and drink, we would only have grown weaker. Instead, we decided to “park,” wait, and rebuild our energy. We battled the storm only when we had sufficient strength and enough daylight to see and react to the waves. Our strategy was not to defeat the gale but to survive until it blew itself out.

![]()

I looked Janice in the eye. “How long can your competitor continue to give away money?”

“I don’t know,” she said. “He can’t do it forever, but he’s costing us both a lot.”

“Quite a storm you’re facing,” I said. “Do you think it’s best to lower your prices, or heave to? You’re going to be stuck in a storm either way. You might not put any miles behind you, but if you wait him out, you won’t burn your resources, either.”

Janice closed her eyes, took a deep breath, and nodded. “They’re spending a lot of money, hoping to sustain conflict long enough to bury me.”

“Meanwhile,” I prompted her, “work on telling a different story. Your competition’s story is all about price. Some clients only care about that, and you may lose them, but storytellers switch the conversation from price to…” I waited for her to fill in the blank.

“Value,” she said. “I’ve got the best service and support in the industry.”

“So when will those lost customers find their way back to you?”

She thought for a moment and then smiled. “Probably when they get tired of battling their first storm and just need to work with a company that takes care of business by taking care of them.”

![]()

In storms of life and business, it requires immense energy to sustain conflict. Dangerous and destructive forces require attention and—at the appropriate times—resistance, but often the best strategy is to park and wait for the tempest to subside.