Confirmation Bias: Storytelling at Your front Door

We give more weight to evidence that supports what we like—a phenomenon called, “confirmation bias.” Belief is often based as much on what we want to be true as on what we determine to be true through direct observation. Data, science, and empirical observation are insufficient to change our hearts and minds when we are entranced by a compelling story, but the consequences of willing suspension of disbelief are dire.

We give more weight to evidence that supports what we like—a phenomenon called, “confirmation bias.” Belief is often based as much on what we want to be true as on what we determine to be true through direct observation. Data, science, and empirical observation are insufficient to change our hearts and minds when we are entranced by a compelling story, but the consequences of willing suspension of disbelief are dire.

![]()

My daughter and I were watching a documentary about disappearing rainforests. At the end, she asked me a simple question: “Why don’t we just stop cutting them down?”

“That does seem like an obvious solution,” I replied, “but destroying jungle habitats is actually a symptom of a much more serious problem called ‘confirmation bias.’ I’ll share a story that explains it.”

![]()

After arriving at the marina, I searched for my boat keys, but they were nowhere to be found. The stainless steel lock securing my boat’s companionway was strong and well-protected. Hiring a locksmith and rowing them out to open that lock would be time-consuming and expensive.

A few minutes of research provided an alternative solution that cost me nearly nothing. After watching a YouTube® video that demonstrated how to pick and open a discus lock, I ordered a set of lock-picking tools on Amazon.com and practiced with some transparent locks. I was in in a matter of seconds.

I had to wonder, though … who else was in? Was a false story of security the only thing that stood between my valued possessions and the greedy hands of some second-rate burglar who had watched the same videos I had? What about my house? Is my front door as good as wide-open to intruders while my family sleeps?

Door locks come in a variety of “pick-resistant” forms, but clever techniques for cracking the latest “high-security” locks can be found online. It turns out that most locks are easy to pick. Locks are just logic puzzles to an entire community of “pickers” who race to be first to post “the solution” online. Unless you install an expensive and sophisticated deterrent, your security depends mostly on the flimsy notion that would-be intruders are too polite to break your doors and windows.

Confirmation bias makes us prefer the story that “thieves are creatures of opportunity.” We like to believe that “the bad guys” are looking for doors that have been left unlocked, that they’re ready to prey on someone else’s mistake. The story that your front door is no more secure when locked than open is one that makes us uncomfortable.

Some people react to this with anger. Why are you making this information public? You are the one threatening my security by letting the world know how vulnerable my home is. But this information is already public. Burglars know how to get in. Is your anger a response to the information or to the collapse of your house-of-cards security story?

If you’re like most people, you’ll file this story under “interesting information,” and continue to use the same locks you’ve always used. Confirmation bias leads us to accept a more comforting story. We prefer “evidence” that confirms what we want to believe.When was the last time anyone entered uninvited? After so many days without a home invasion, why assume there’s a threat? If you do nothing, you’ll probably continue to experience a low incidence of break-ins.

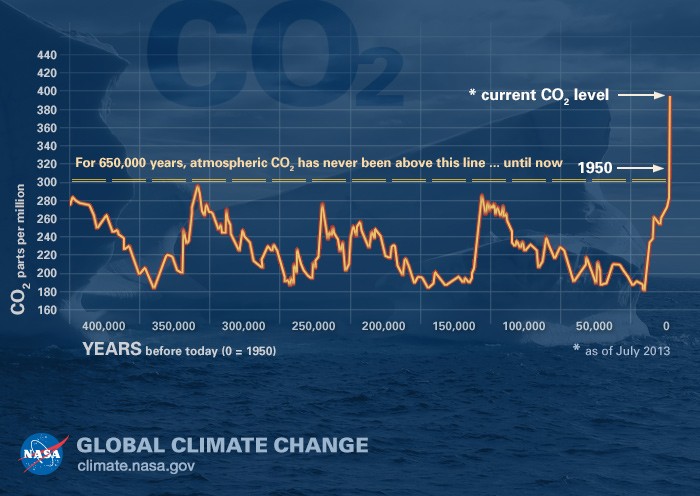

But the ill-effects of confirmation bias extend beyond our front doors. Are raging wildfires, powerful hurricanes, and increasing ocean temperatures signs of environmental change? Or do you prefer the story that climate change is a natural, cyclical phenomenon? How does the evidence—the historically unprecedented rise in atmospheric carbon dioxide since the industrial revolution—affect your willingness to embrace the story of man-made climate change? Will you swallow this bitter pill or attempt to discredit the doctors who prescribed it? Why?

Just as a cheap set of tools provides easy access to your home, a feelgood story is sufficient to unlock and invade an unprotected mind. Do you trust what you see in print and on television because it’s polished and well-produced, or do you “read between the lines,” verify allegations, and fact-check? If we are to return to “indivisible with liberty and justice for all”—if we are to create a strong democracy where discriminating voters are informed by facts instead of blinded by red and blue flags—if we are to preserve our beautiful planet—we must reinforce our weak locks with self-awareness, skepticism, and objectivity. The stories we believe and act on must be the authentic ones—not the ones we like the best.