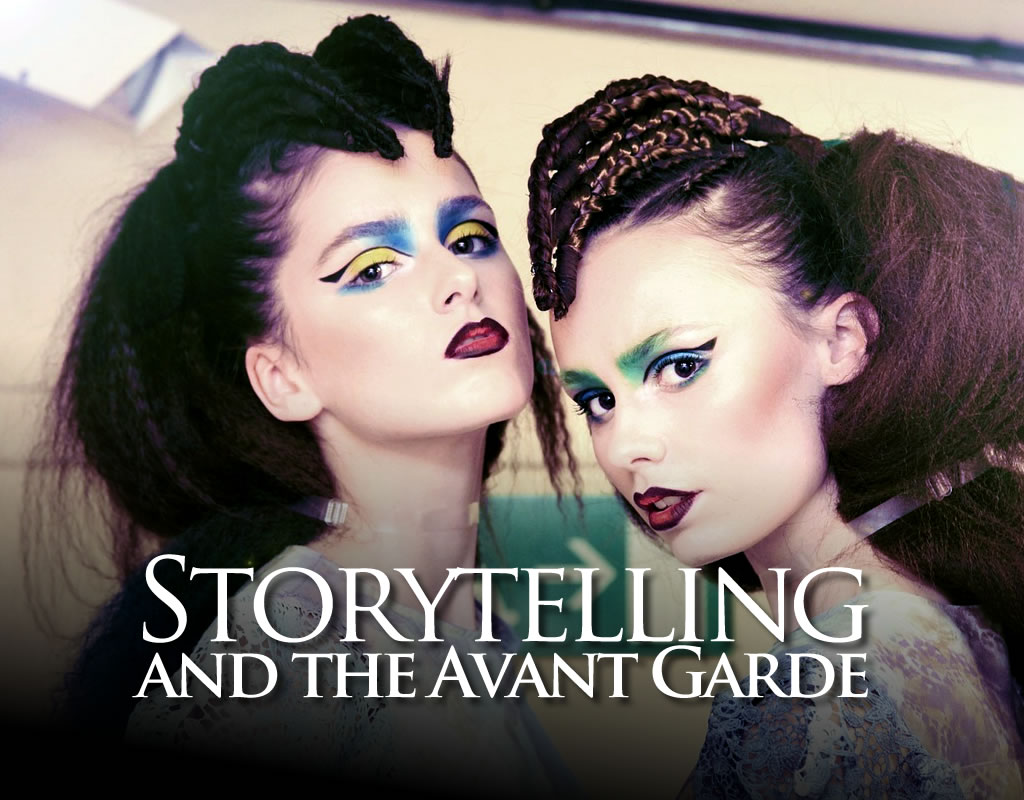

Storytelling and The Avant Garde

An accomplished jazz musician, educator, and friend pointed out that too many virtuosic young players blow a lot of noisy notes with fire and conviction, ignore the structure of the music, and brand themselves as “avant garde.” To his ears, their music sounds inauthentic. To play true avant-garde music, the musician (or any other kind of artist) must understand the forms and structures that “free form” styles were conceived to rebel against. What the faux avant garde lacks is connection to the story—to the avant garde’s very reason for being.

Saint Simonian Olinde Rodrigues’s essay, L’artiste, le savant et l’industriel (The artist, the scientist and the industrialist, 1825) contains the first recorded use of “avant-garde” in its customary sense. Rodrigues calls on artists to “serve as [the people’s] avant-garde,” insisting that “the power of the arts is … the most immediate … way” to social, political, and economic reform.

Music is a continuum. Serious musicians study and are influenced by one or more spectra on that continuum. To claim only a single point, play your isolationism with conviction, and justify that with the label “avant garde” is ignorant. Throughout history, avant garde movements in music, art, and design have sprung up as rebellion against political, artistic, spiritual, and societal structure. Without awareness of the structure, there is no rebellion. Without rebellion, there is no avant garde. Copied and stripped of its context, the avant garde is noise.

Jazz is a language. It has syntax, grammar, vocabulary, slang, and phrases that evolve from innovative to cliché and then get replaced by new ones. As such, jazz is a vehicle for storytelling, and the question of how to assess the legitimacy of avant garde expression can be viewed through that lens.

Scholars of English read the classics. They study the evolution of the tongue back to some relevant point in history. The serious ones study Latin and Greek; they look all the way back to the foundations of modern language and civilization. I have described jazz as the “Latin of popular music” to younger musicians who don’t “get it” and wonder why their teachers want them to study “that old stuff,” but to the point about the relationship of the avant-garde to traditional roots, consider the following analogy:

I speak enough Spanish to find my way around, greet my Latino friends, and keep my Über driver on-course, but I am by no means fluent. If I were to start adding Os to the ends of my wordios and pretendiendo to be an “avant garde” speaker of Españolio, my Latino friends would quickly disown me (and with good reason). But, if I could speak traditional Spanish eloquently, these same twisted usages might be granted a poetic license. If I own the language, I own the right to twist it (and as a writer and editor, I make English my playground in ways a non-native speaker would never credibly do).

Expression—storytelling—can be judged in the moment or against the background of the times, history, and the artist’s intentions. Picasso made a famous bull’s head sculpture out of a bicycle seat and some old handlebars. In and of itself, it’s unremarkable, and many critics found it unworthy of the famous artist—a gimmick. But as a commentary on what Franco had done to Spain, it was brilliant—not only in this simple junk collection’s ability to make a statement, but in its ability to make that statement in a way that wouldn’t offend the fascists and get Picasso killed. Had the bull’s head been made at the same time by an African or Swedish artist, it very well might have ended up hanging in obscurity in someone’s garage until it rusted its way to the dump.

Languages, be they spoken or musical, are vehicles for storytelling. A story contains conflict and transformation. The faux avant garde is ignorant of the conflict. Its adherents perform “happily ever after” without ever trying to win the hand of the maiden, kill the dragon, or search for a way to cross the river.

Discerning ears can hear and feel the difference between someone who makes the sounds and someone who knows the story.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2FIt4g9fgcgWatch the great Charlie Chaplain in Modern Times (1936), an early motion picture with an embedded soundtrack (the scene actually begins with a title card). Quite possibly, it was this scene that gave rise to the expression, “off the cuff.” When the lyrics written on Charlie’s cuff fly off, he’s forced to improvise his lyrics. Listen to how his lyrics are tied to English words (“taxi meter”) and European dialects. Instead of spewing random syllables, he connects his gibberish to language the audience is familiar with. And of course, the master of the silent film has much to teach us about body language. The gestures (pulling someone close for a kiss, pulling down the window blind, etc.) add another layer of incongruity when combined with the words. Given the new-at-the-time medium of “talking” pictures, this is true avante-garde performance—something new with roots in the familiar.