Abraham Lincoln’s famous Gettysburg address has been recorded by numerous orators over the years, including Orson Welles, but few of these works suggest that the speakers did anything more than read with conviction. How do you reconstruct a speech that was delivered 150 years ago—in the days before microphones, amplifiers, and recording technology? Historical research and analysis of the text reveal pathways to how Lincoln may have delivered his iconic Gettysburg Address.

Scholars debate which of the five existing copies of the Gettysburg Address was the one read in 1863. Newspaper accounts of the speech contain other variations. Though small differences between them offer opportunities to interpret the text, this article relies on the generally accepted version that Abraham Lincoln affixed with his signature.

Four score and seven years ago our fathers brought forth on this continent, a new nation, conceived in Liberty, and dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal.

Now we are engaged in a great Civil War, testing whether that nation, or any nation so conceived and so dedicated, can long endure. We are met on a great battle-field of that war. We have come to dedicate a portion of that field as a final resting place for those who here gave their lives that that nation might live. It is altogether fitting and proper that we should do this.

But, in a larger sense, we can not dedicate—we can not consecrate—we can not hallow—this ground. The brave men, living and dead, who struggled here, have consecrated it, far above our poor power to add or detract. The world will little note, nor long remember what we say here, but it can never forget what they did here. It is for us the living, rather, to be dedicated here to the unfinished work which they who fought here have thus far so nobly advanced. It is rather for us to be here dedicated to the great task remaining before us—that from these honored dead we take increased devotion to that cause for which they gave the last full measure of devotion—that we here highly resolve that these dead shall not have died in vain—that this nation, under God, shall have a new birth of freedom—and that government of the people, by the people, for the people, shall not perish from the earth.

In what style did Abraham Lincoln deliver this iconic speech? Lincoln left us only the text. Clarity is found by researching the historical context. What was the occasion? Are descriptions by eyewitnesses available?

Historical Context

Following the Battle of Gettysburg on July 1–3, 1863, fallen Union soldiers were removed from battlefield graves and reburied at the National Cemetery at Gettysburg. Reinterment of soldiers’ remains was less than half-complete on the day of the ceremony. David Wills of the committee for the November 19 Consecration of the National Cemetery at Gettysburg, wrote, to Lincoln: “It is the desire that, after the oration, you, as Chief Executive of the nation, formally set apart these grounds to their sacred use by a few appropriate remarks.” “After the oration” refers to the two-hour(!) address[1] given by Edward Everett that preceded Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address. We know the occasion was a solemn and sacred one. Burials of war dead were still actively under way. Lincoln’s tone would likely have been serious and powerful.

We can also assume that by the time Lincoln spoke, the crowd would have been tired from standing and listing to Edward Everett for two hours. Even on a sunny November day in Pennsylvania, the temperature would probably not have exceeded 55ºF/13ºC.

Lincoln was an experienced orator who understood that a brief address would be a gift to his audience. That made his message more powerful. And because microphones or public address systems hadn’t been invented at that time, presenters valued vocal projection as a fundamental platform skill. Audiences knew that the success of a speaker rested on their own ability to stand still and silent. Lincoln’s delivery to an outdoor crowd of 15,000 people would have been measured, clear, and forceful.

Eyewitness Reports

What did attendees say about Lincoln’s address?

William R. Rathvon describes that Lincoln stepped forward and “with a manner serious almost to sadness, gave his brief address. … As Lincoln spoke, he had one hand on each side of his manuscript (and) spoke in a most deliberate manner, and with such a forceful and articulate expression that he could be heard by all of that immense throng,”

Philip Bikle recalled. “There was no gesture except with both hands up and down, grasping the manuscript which he did not seem to need, as he looked at it so seldom.”

Sarah A. Cooke Myers, who was nineteen when she attended the ceremony, suggested that a dignified silence followed Lincoln’s speech: “I was close to the President and heard all of the Address, but it seemed short. Then there was an impressive silence …. There was no applause when he stopped speaking.”

According to historian Shelby Foote, after Lincoln’s presentation, the applause was delayed, scattered, and “barely polite.”

According to Pennsylvania Governor Andrew Gregg Curtin, “He pronounced that speech in a voice that all the multitude heard. The crowd was hushed into silence because the President stood before them … It was so impressive!”

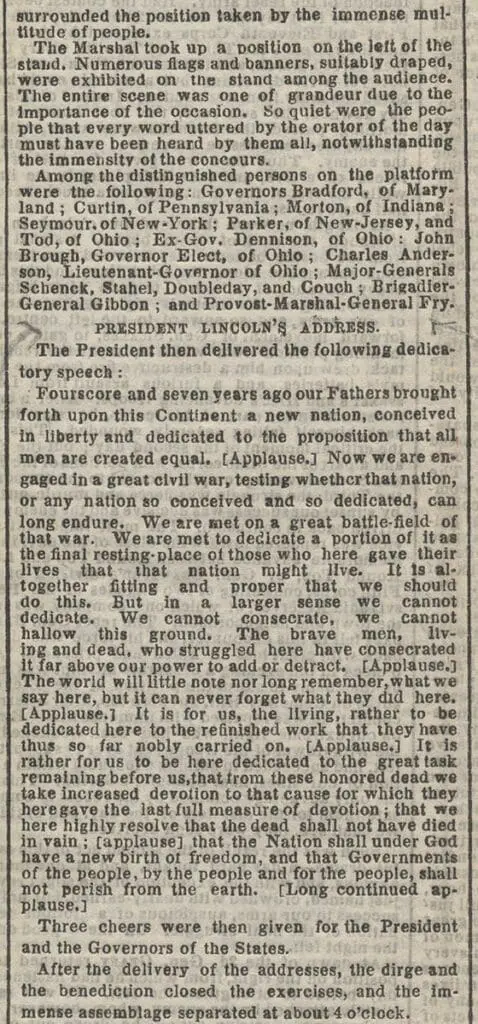

But The New York Times article from November 20, 1863, indicates Lincoln’s speech was interrupted five times by applause and was followed by “long, continued applause.”

But The New York Times article from November 20, 1863, indicates Lincoln’s speech was interrupted five times by applause and was followed by “long, continued applause.”

The newspaper article includes a transcript of the speech, and since the reporter likely had no access to the manuscript, this may well be the version that Lincoln read. Differences between the newspaper transcript and the manuscript may be accurate, or they may be the result of the reporter’s poor transcription. No one will ever know.

The transcript in the article has the moments of supposed applause inserted—a valuable guide for future orators … if we assume that reports of “delayed, scattered, and barely polite” applause and “no applause when he stopped speaking” are inaccurate and that the newspaper’s reports of “long continued applause” and “three cheers” were not editorial hyperbole offered more for the sake of engaging readers than recording fact. If the majority of the witness accounts are accurate (and contemporary biases about objective reporting allowed to prevail), Lincoln’s address may not have been the big crowd-pleaser it is thought to have been—or given the solemnity of the occasion and the presence of the speaker, it may indeed have been followed by “an impressive silence.”

Though several newspapers inserted “[Applause]” into the transcript, most relied on the Associated Press, which immediately sent out the speech from Gettysburg by telegraph.[2] During this time when the Civil War was still raging , the news media may well have decided to rally the nation by embellishing the truth about the audience’s response—which suggests that “fake news” is no new phenomenon.

Given that there were 15,000 people in the crowd, it’s unlikely that Lincoln’s address was even audible to most of them. Those close to the platform may have applauded enthusiastically. Those more than fifty feet away may have responded politely to the applause in front of them, but would not have known what they were applauding for. Though accounts range from “no applause at all” to “three cheers when he was done,” those positioned in different parts of the crowd would have had different experiences.

The Words and the Message

To understand and convey Lincoln’s message, one must go beyond eloquent reading. The words are poetic and powerful, but careful analysis reveals an important theme. Lincoln begins by establishing his purpose—that “We have come to dedicate this field as a last resting place for those who here gave their lives that this nation might live.” He goes on to acknowledge that “it is altogether fitting and proper that we should do this,” and then he expands on the motif of dedication.

“But in a larger sense, we cannot dedicate, we cannot consecrate, we cannot hallow this ground. The brave men, living and dead, who struggled here have consecrated it far above our poor power to add or detract.”

At first glance, this appears to be a straightforward “rule of threes” structure where a selection of three phrases is delivered with rising emphasis. Lincoln’s “larger sense” point, however—which he expands on throughout the rest of the speech—is that those who fell in battle have already done the work of “dedicating” the field. He suggests that “we, the living” should be dedicated to their cause, to completing the “unfinished work which they who struggled here have thus far so nobly advanced.” This suggests a different emphasis for this pivotal phrase which introduces a play on the concept of dedication. “Dedicating” a cemetery is trivial compared to being “dedicated” to fulfilling the mission that landed people in the cemeteries. A likely interpretation (though I have found no example of a recorded reading that uses it):

“But in a larger sense, we cannot dedicate, we cannot consecrate, we cannot hallow this ground. The brave men, living and dead, who struggled here have consecrated it far above our poor power to add or detract.”

The distinction between we, the living and they, the dead continues:

The world will little note, nor long remember what we say here, but it can never forget what they did here.

The above line may even contain a hint of sarcasm. Was Lincoln’s remark a subtle dig at the idea of standing around and talking about those who gave their lives when the war was not yet won? Or even a jab at Edward Everett’s two-hour oration—which Lincoln probably sat through? These words and the overall brevity of Lincoln’s address support the idea that Lincoln was all for “shutting up and getting on with what needs to be done.” He continues with the we/they/now theme:

It is for us the living, rather, to be dedicated here to the unfinished work which they who fought here have thus far so nobly advanced.

It is rather for us to be here dedicated to the great task remaining before us—that from these honored dead we take increased devotion to that cause for which they gave the last full measure of devotion—that we here highly resolve that these dead shall not have died in vain.

Using a traditional “rule of threes” approach that forever became associated with core American political values, Lincoln closed his Gettysburg Address with a final aspiration for his audience:

… that this nation, under God, shall have a new birth of freedom—and that government of the people, by the people, for the people, shall not perish from the earth.

Powerful words falter without powerful delivery, but powerful delivery can mask weak interpretation to the detriment of the message. Though the original sounds and intentions of Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address may be lost to history, careful scrutiny of both the text and the context reveals the path to faithful, if not accurate, recreations of historic orations.

[1] https://voicesofdemocracy.umd.edu/everett-gettysburg-address-speech-text/

[2] https://yorkblog.com/yorkspast/president-lincoln-was-interrupted-five-times-with-applause-during-his-gettysburg-address/